RECENT WRITING

•

RECENT WRITING •

PLAYING TO THE END: A DISPATCH FROM WIMBLEDON

The Point | July 17, 2024

I cannot stop thinking about this: how Djokovic, who has secured nearly every important men’s record, raced to return to competition, battling through surgery, recovery, pain and the denigration of crowds. Why would a man disparaged as a villain, as a feaster of broken hearts, continue to fight when he’s already won everything there is to win? How much suffering is the all-time champion willing to endure when he has already secured immortality?

…

There is something spectacular and heartbreaking about watching the greats fade. […]

THE FIRST ENCHANTMENT: TEN YEARS OF THE GREAT BEAUTY

The Point | March 8, 2024

The Great Beauty taught me to seek a life of wisdom, vitality and deepened experience. At the same time, the illusions corroding the protagonists enchanted me: I bought white trousers, many-colored blazers, pocket squares and two-toned brogues. I traveled to Rome, the most necessary trip of my life. When I taught a college class for the first time, I could only think to show the students Jep’s final monologue. I was determined to learn the secrets of Sorrentino’s art; I purchased the Criterion edition and sat down to reverse engineer it, scene by scene, pausing every frame to reconstruct the screenplay in a special notebook I bought, as if one could capture the grandeur of the Colosseum by taking it apart brick by brick. […]

“A NEW LIFE FOR US”: ZELDA AND THE FUTURE OF STORIES

PUBLIC BOOKS | December 6, 2023

After a half-hour of waiting for the employees to retrieve the large boxes from behind the locked door at the back, I began to understand what we were all doing there. We were searching for a deep encounter with ourselves and with the imaginations of others, like the hypebeasts who lined up in their too-clean sneakers for each limited release, outsiders assembling on the occasion of the new, seeking an encounter with beauty. Like desperate dreamers, like Koltins gathering in the dark: feeding ourselves on games and midnight hours, all in the earnest search for the transformation of the self. […]

WHY CLIMATE PROTESTERS ARE FOCUSING ON TENNIS

The New Republic | September 9, 2023

I empathize with the bitter masses: tennis is a beautiful joy; adulthood is exhausting, frustrating, and relentless with its responsibilities and disappointments. Yet I cannot forget the repeated image of one or two or three fans standing up from tens of thousands on Thursday night to deliver monologues at the end of the world. I cannot stop thinking about how they were led out of the arena, the audience cursing and jeering, with their heads lowered or raised in defiance.

Human-caused climate change has been around for less time than tennis, but it will leave its scars on the earth for longer—much longer, millennia and millennia longer—than the outlines of our hardcourts, than our fleeting forehands, backhands, and break points. […]

YU-GI-OH! AND US: REMEMBERING THE FATHER OF MILLENNIAL CHILDHOOD DREAMS

THE SMART SET | July 28, 2022

Why did we love those fantastical drawings, and why did it hurt when I lost them to hot water? What did Takahashi know about us that nobody else did?

…

This is why Yu-Gi-Oh! mattered to us, why I couldn’t sleep for nights because of the loss of my favorite cards: it represented the challenge to improve and overcome yourself, to debate and listen to the voice within your head, and to come to terms with having someone inside you who is both you and not you — who is better, stronger, smarter, wiser and more mature, but also distant, capricious, and unknowable. Takahashi’s fictions visualized the reality that we carry a self within us who is different from the one everyone can see. […]

-

ON HOW TO DRAW A NOVEL, ESSAYS AND DRAWINGS BY MARTÍN SOLARES

ON THE SEAWALL | January 9, 2024

Solares points out that “the good novelist multiplies the reader without their even noticing,” a marvelous and accurate image, because is it not true that, once an author moves us with her prose, once we pass through the world of a novel, we emerge as more than what we were when we began, as multiples of ourselves? […] -

CHILEAN POET

CHICAGO REVIEW OF BOOKS | February 22, 2022

Some people live without needing literature. They summer in vacation homes, host parties, marry sweethearts with perfect smiles, bear children who will become not followers but influencers, and pass peacefully in their sleep with smooth faces. The rest of us read books. We chase romance at bonfires and dive bars, trudge through blizzards for groceries, quarrel with our parents about trifles from our youth, and crawl to the ends of our workdays and nights. We are eternal children: our bodies widen, wrinkle, stubble, and sag, but we look out from them as nine-year-olds, forever, with amusement, hope, desperation, and wonder. We do not have what the others have: this is why we imagine and read. […] -

MARIE DARRIEUSSECQ PLUMBS THE DEPTHS OF SLEEPLESS NIGHTS

THE MILLIONS | October 30, 2023

I will never forget the first time I saw the devil—leering at me, lurking in the corner of the room, glowing red and approaching my motionless body. I was caught between sleep and waking; I blinked furiously; I struggled to rouse my heavy limbs as he raised his hand to my face. I could not even muster the strength to open my mouth and cry out, help, mommy, help, the monster will get me— […]

-

NEW WAYS OF WRITING THE DYING WORLD

PLOUGHSHARES | January 20, 2022

Czesław Milosz’s most famous poem asks, “What is poetry which does not save / Nations or people?” He posed the question in the ruins of Warsaw in 1945. Now, more than seventy-five years later, is it poetry or the novel that will save us from our demise? Or the movie, or the pop song? Can we believe that one book, written in short sections with run-on sentences, will rescue us? […]

-

HOW TO START WRITING (AND WHEN TO STOP)

CHICAGO REVIEW OF BOOKS | October 5, 2021

Our writing quotations, in slightly different ways, all say the same thing: attend to the world.

Szymborska knows this. She knows that offering technical or theoretical opinions will not inspire great novels or poems. She knows that chairiting compliments, mandating reading, or proffering degrees will not make a writer. A writer makes herself—despite the teachers, institutions, and societal expectations that work to reduce her to a boring, clichéd, dead-in-the-imagination existence that the rest of society accepts. Because writing, before anything else, springs from personal vision, a self-sought taste, an inner voice, bravery in choosing solitude, and hours alone with the keyboard and pen. And this is just another grand statement about the art. It will mean nothing for the young writer until she lives it herself, alone, and looks back on what she has made. […]

-

IN MEMORY OF MEMORY

ANOTHER CHICAGO MAGAZINE | May 25, 2021

I like to read newly translated authors because they allow you to see a reality different from your own through gentle, patient eyes. If the author is good you start to realize that your reality and theirs are not so different. And you fill with the excitement of understanding despite difference—the miracle of art—and feeling like you have discovered something valuable, a secret you want to save for yourself but also share in with the uninitiated, who do not yet know what awaits them. […]

READING THE BOOKS OF JACOB WITH—AND AGAINST—THE RIVERHEAD READING GUIDE

The Los Angeles Review of Books | March 1, 2022

The ideal reader’s guide, then, would not be mass-produced for all readers but would be individualized for each reader. These guides would result from hours of interviews with every reader and intensive research into their lives, the many motivations and failed dreams that determined their character, and the countless unspoken influences they may not be aware of but that the researcher can perceive. The guide would be written in a personal hand, aware of each reader’s likes and dislikes, wants and needs. It would guide us not to the major events on each page but to ourselves. This would be impossible, of course, since we are libraries all; no single guide, even the most well-researched one, could suffice.

…

If there were a guide for every reader, mine would include notes on being called the wrong name. The reader’s guide to my life would be a guide to being misread, a guide to growing up mispronounced: when they tried my name, strange sounds came from American mouths. […]

“ASKING WHAT’S REAL AND WHAT’S NOT”: A CONVERSATION WITH MADELEINE GROSS

THE SMART SET | February 28, 2022

What is it about Gross’s work that moves me so much? It is the aesthetic boldness, the drawing the eye with leading lines up a photographed rue to a painted sky. It is the round shapes and soft shades. It is the joy of color and light, represented faithfully in our dismaying times. It is the outlines of women, who rise above their surroundings in mystery and splendor. It is the complement of hyper-detailed photographs and people painted like impressionistic artworks, which approximates how we live more than any other aesthetic or technique, as we pass through our detailed settings to the experiences of other people, who are explosions of feeling and color and memory and expectation and beauty and love and dream. It is this that moves me: the inner world painted on top of the outer. Images true to both the visual and emotional reality of life. Accepting both, not either-or. The dreamed-of and the lived. The poetic and the mundane. Reality. Art. […]

THE DESPERATION AND QUIET RESOLVE OF #DAYINTHELIFE TIKTOK

HYPERALLERGIC | January 31, 2022

But can the genuine penetrate the TikTok voice? Can we find beauty or peace in washed out filters? Can we be healed by the tools that induce our pain?

. . .

My personal resolve, to step away from the bacchanal of validation and pain, may seem impractical to the motivators. And we may be bound in knots we can never undo. Instead, I like to picture the reality at the edges of each frame. The day-in-the-life videos feature unpeopled scenes. The few that include a companion reduce him (often him) to an elbow, a leather shoe. You do not have to strain to imagine the life outside the day-in-the-life: the continual pausing at meals to pan over the food; the conversation-stopping apologies (I need this content); the entreaties to do something again; the slow opening of washer and refrigerator doors (for the seventh time, in an apartment, alone); the desperate semi-furtive movements of the filmmaker’s hands, which seize the pro-sized phone, palm for it under tables, throw open purses and jacket pockets for it, and thrust it forward to record. […]

ON BILL NYE AND OUR SEARCH FOR A SAVIOR AGAINST CLIMATE CHANGE

UW–Madison Office of Sustainability | May 19, 2022

At the precipice of the end of the world, we are desperate for a perfect hero, desperate for someone trustworthy and honest and noble, desperate for the character of the wise, passionate, communicative scientist we met in grade school. But in our times there are no earthly gods: they grow old, sign brand deals, become angry, tired, self-certain, and vague. The Nye everyone came to see that night was not the Nye sitting on stage. The Nye everyone came to see only lives in our dreams: a perfect savior who will wipe centuries of human cruelty from the world and rescue vulnerable ecosystems, species, and people from the permanent, destructive self-aggrandizement and ignorance of our race. This is what the young shout, wave their hands, clap, scream, and cheer for: not science, not celebrity, but miracle. […]

UNFORCED ERRORS: THE TRAGICOMEDY OF NOVAK DJOKOVIC

THE POINT | January 27, 2022

Every night for two and a half months, Novak Djokovic woke to sirens and fled to his grandfather’s basement as bombs fell on Belgrade. He was an anonymous child in a country without global legends. One night his father placed ten Deutschmarks on the table: this was all they had. In childhood he also discovered sport. A few years earlier, he stood at the fence to watch a tennis camp in the Kopaonik mountains, and the coach, Jelena Gencic, invited him to play. She developed him into a player and man, introducing him to forehands and backhands, Pushkin and Beethoven. She taught him the short-angle crosscourt backhand; when she played Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, goosebumps rose all over his body. […]

EVERYWHERE BERGAMO (FICTION)

WORLD LITERATURE TODAY | August 30, 2022

What went on behind those walls? Those closed doors, those one-bedroom, two-bedroom units? Those midrises and those studio walkups? In those little rooms obscured by neighbors’ bodies, which he could glimpse over their shoulders, seeing a plant, a metal bookcase, ripe fruits on the counter as the keys jangled and the door shut? […]

THE STORY OF MASS SHOOTINGS, REPEATED IN HIGHLAND PARK (OP-ED)

THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE | July 5, 2022

My generation grew up in the 1990s and 2000s learning the story of civilian massacre. Mass shootings remained behind the TV screen, uncanny horrors that seemed too distant to be human. But in school we huddled in dark corners in preparation for our death. We were forced to see ourselves in the story. I imagined what I would do — perhaps fleeing, perhaps defending those beside me in heroism that would prove my character to others and to myself — as well as what I would say at the microphone as a weeping family member or friend. All of us did this, and our country has permitted enough mass shootings that we do not only fear them but also are now waiting for our turn to be the victims running from bullets and shrieks.

I have reached the part of the op-ed when the writer typically offers a promising cliché: We must unite, we will change our story, etc. I can’t. […]

THE POETRY OF WISŁAWA SZYMBORSKA AND ALEJANDRO ZAMBRA’S BOOK REVIEWS

PLOUGHSHARES | December 22, 2021

What else makes a book review? Adjectives, snappy-one liners. Paragraphs without transitions. Overgeneralizations and judgments. Precisely imprecise star ratings. John Updike’s guidelines include ascertaining the author’s goals, direct quotation, plot summary (not too much), and, if deeming the book a failure, pointing readers to a successful example. The review also depends on the author and venue: a magazine like The New Yorker, for example, allows the writer more space to explore a book’s ideas and techniques. The reviewer earns these inches in newspapers if they are a well-regarded novelist, like Knausgaard writing about Michel Houellebecq’s Submission (2015) or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie about President Barack Obama’s A Promised Land (2020). In these instances, the review becomes a space to explore the reviewer’s self, an opportunity to show how their way of reading novels can illuminate a great new work for us.

Simple enough. But what about the Neanderthal’s tears? Sometimes I enjoy reviews, and their summaries guide me to books I will cherish. But why don’t I feel anything when I read them? Why do I long for something else? […]

OLGA TOKARCZUK’S RADICAL TENDERNESS

THE YALE REVIEW | February 22, 2021

In October 2019, when the Swedish Academy’s press secretary announced Olga Tokarczuk as the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, I was lying in bed with my eyes closed, holding a phone that was livestreaming the ceremony. For years I had woken at 6 a.m. on the day the laureate would be named, hoping to discover a great author in a language I did not know or possibly one who wrote in my ancestors’ tongue. The secretary spoke in Swedish, so I did not understand anything until he said “Olga Tokarczuk”: yes, that was Polish, a language my parents and my grandparents and my great-grandparents and I understood. I spent the morning on the phone, writing and speaking to my family about the news, and thinking about how writing allows one to communicate with others different from oneself, miles away, unlocking however briefly the prison of one’s solitude. […]

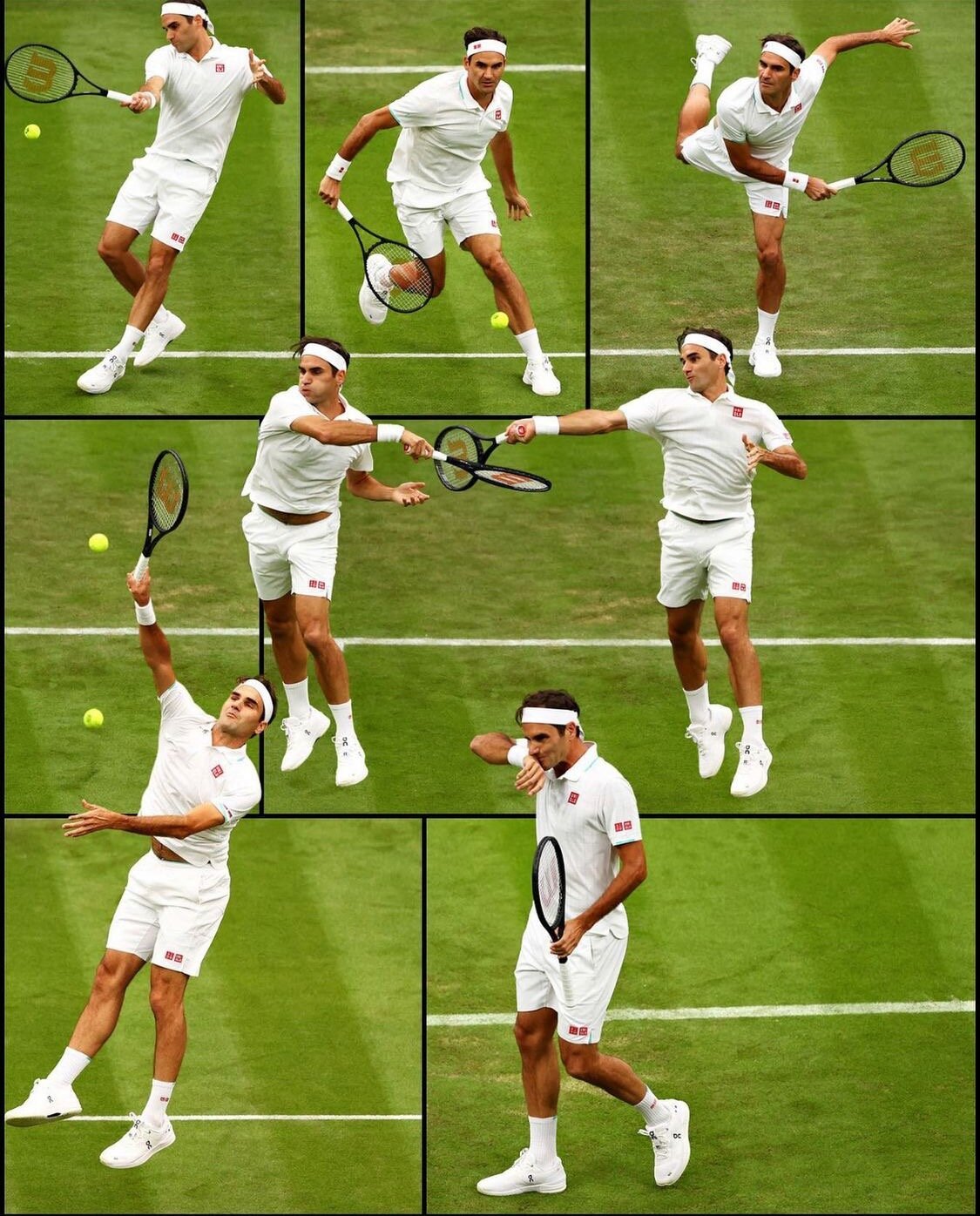

The Master: The Long Run and Beautiful Game of Roger Federer

COMPULSIVE READER | September 8, 2021

Roger Federer’s life story could be arranged by scenes of crying: on court, when he struggled with emotion in youth; when he ran out onto the streets of Toronto, only 20 years old, after learning that his coach died; after beating Pete Sampras at Wimbledon in 2001; during his victory speech after his first major; after his loss to Rafael Nadal at the Australian Open in 2009 (“God,” he said to the crowd, “it’s killing me”); when he fell to his knees as he won his only French Open championship; when he jumped in disbelief with his miraculous victory against Nadal at the 2017 Australian Open for an eighteenth Grand Slam; and in his 2019 defeat to Novak Djokovic at Wimbledon, after holding match points at 8-7, 40–15, when he made it to the locker room and collapsed. […]

TOILETS, PAPERS, CARDBOARD BOXES OF A COUNTRY’S SECRETS

THE SMART SET | January 11, 2024

When we think of iconic images, those that tell the story of a nation and its people, we imagine art-photography, masterful stills of gestures and chiaroscuros that illuminate a person’s character and hold the unseen captive for our witness. These images come to represent our loneliness, our bravery and empathy, our fracture and pain. The image of the boxes in Trump’s bathroom is not artful; it is not part of the aesthetic tradition of front-page photographs and National Geographic’s Photos of the Year. Yet it illuminates as much as the paintings and photographs in Guggenheim, and it portrays the strange, absurd state of politics in 21st-century America.

…

With Trump comes the surprise that oftentimes these secret dealings, the private lives of presidents and kings, might be more banal than the little dramas of our own. That the images a country uses to brand itself — flags, crests, military uniforms and vehicles, podiums, manicured gardens and lawns — sometimes give way to the other images that define a country: landfills, fires, handcuffs, corpses, guns. […]

-

HOW WE CREATE OURSELVES: SECOND PLACE

THE RUMPUS | August 4, 2021

You can hear the difference in Rachel Cusk’s new novel. Her Outline trilogy redefined the narrator, as it abandoned characterization, plot, and description for the reported speech of others set in a cool, distant tone. Reading those books felt like eavesdropping on the calm, perceptive conversations of strangers in cafes. The narrator, Faye, listens more than she speaks, and she creates her presence through her absence, through the outline she forms in her milieu.

From the first sentence, then, Second Place announces itself as different. […]

-

LEGENDS AND GHOSTS IN THE COLLECTED BREECE D’J PANCAKE

THE SMART SET | December 7, 2020

I first heard of Breece D’J Pancake in a small pizzeria an hour west of Chicago. I had not been tending the bar that summer night, but Rae was, and when I came in to pick up a pizza she said to the lone man at the counter, writing, he does writing, and she called to me from behind the bar, saying, Honey, honey, O, honey, you need to talk to this man, he is a writer, too. […] -

THE LOST SOUL

CULTURE.PL | February 23, 2021

After publishing ‘The Books of Jacob’ in Poland in 2013, the historical epic that has been considered her greatest work and that she has said left her mentally and physically depleted, Olga Tokarczuk wrote the text for a picture book. It is as if, after filling hundreds of pages with grand characters on her own, with voices from all the choirs of life and time, she needed to reach for something more collaborative, for something other than voices and words. […]

-

SEEING FURTHER

THE MILLIONS | January 30, 2025

What, then, is in this novel? The past: details watched in slow motion. Rain and wind, the musty scent of damp wood, heavy felt curtains, people smoking in screening rooms, “plumes rising before the image and floating in the air.” Projectors thrumming, clicking with life. Concession stands, coat checks, “old-fashioned tear-off tickets made of a thin textured cardboard,” and celluloid film strips, teeming with “an entirely distinct, unrepeatable magic”—“beauties from a different time.” … Kinsky’s narrator asks. “Were there still small residues of images and scenes sticking to the edges of the holes and damaged spots?” […]

-

QUESTION 7

WORLD LITERATURE TODAY | January 2025 (Vol. 99, no. 1)

Question 7 is one of those rare books that contains too much life—too much beauty and pain—to squeeze into the narrow columns of a review. Instead, I’ll turn back to summary. Throughout the book, Flanagan writes of rivers. Flanagan describes how his mother took him to a river at a young age and how “I didn’t know it was a river. I thought it was the world, that the world moved.” And “when the subject was sad or serious,” his father “would smile wanly, his face turning inside out, a concertina of wrinkles compressing his eyes into wry sunken currants, and from him would flow a riversong of stories.” […]

-

THE MYSTERIOUS CORRESPONDENT

ON THE SEAWALL | April 13, 2021

In the 1890s, two decades before the publication of In Search of Lost Time, Marcel Proust wrote short stories. He printed 11 of these in Pleasures and Days but abandoned the rest as handwritten, unpublished drafts marked by insertions and deletions. Bernard de Fallois, a Proust scholar, discovered the stories in the 1950s, along with Jean Santeuil and Against Sainte-Beuve. But while the latter were published then, the stories remained forgotten in the archive until 2019. […]

TEACHING THE OBJECT ESSAY; OR, WHO ARE THE WRITERS NOW?

THE SMART SET | April 15, 2021

In 2017 I entered the PhD program at UW-Madison because they would pay me to read and secretly I could use most of that time to write. I felt I had wasted the previous year working at a restaurant to pay off loans — not reading, not writing. I had squandered my prose style, I thought, and spent too much time with others. Now, in Wisconsin, people would not matter, and I would become a writer again in my self-exile, armed with solitude, a healthy lonely melancholy, discipline, and books. […]

A FAREWELL TO ADAM ZAGAJEWSKI

WORLD LITERATURE TODAY | April 14, 2021

I was waiting for a tennis court on the lakeshore in Chicago when I read that Adam Zagajewski died. I have always considered tennis like writing: you practice to get into a rhythm, you wait for moments of inspiration, and sometimes you play out your imagination without feeling yourself thinking or moving at all. Zagajewski lived not far from there when he taught at the University of Chicago, and his poetry and essays always described how we live between banal moments of everyday life and sudden rousing flights of inspiration and clarity. I hope he would enjoy my comparison to tennis, as both can pull one into the sublime, though it is too late to ask him now. […]